No Products in the Cart

Winter Wolves and Energy Math: Every Hunt Is a Gamble

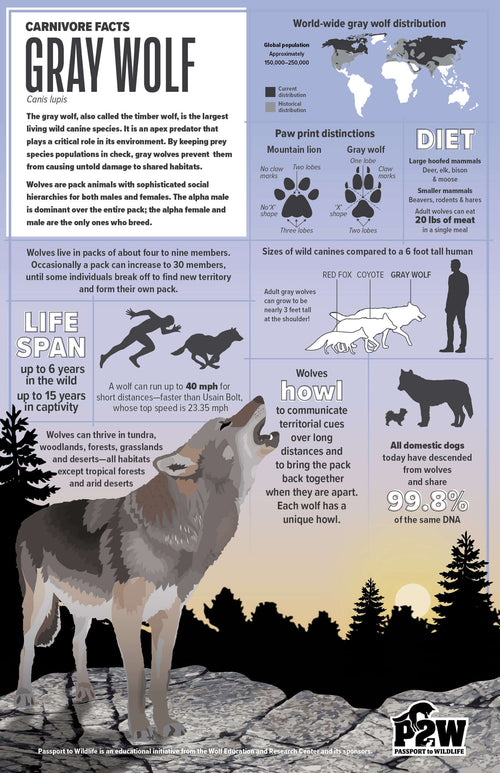

On a cold winter morning, wolf tracks look like a simple story in the snow:

Paw prints. A trail. Maybe a scatter of deer prints nearby.

But for the wolf that left them, that path is part of a much bigger question:

“Did I gain more energy from this hunt than I spent?”

In winter, every decision a wolf makes—how far to walk, which herd to test, when to chase and when to back off—is really a question of energy math. The snow is deeper, the air is colder, and prey are thinner and more cautious. Every hunt becomes a gamble.

That “energy budget” idea is incredibly kid-friendly. It’s the same as asking, “Are you earning more than you’re spending?”—just with calories instead of money. Perfect for simple graphs, story problems, and compare/contrast activities in class.

Why Winter Is So Expensive for Wolves

Wolves are built for motion. Long legs, deep chests, thick winter coats, and big lungs all say: “I’m made to travel.” That’s exactly what packs do—covering miles of territory every day in search of food.

But motion in winter comes at a higher price.

- The cold air steals heat, so wolves burn more calories just to stay warm.

- Snow and ice make every step heavier and slipperier.

- Prey animals are hungry too, so they’re jumpy, wary, and harder to catch.

Even on a day with no successful hunt, a pack is still paying for:

- Heat (staying warm)

- Miles (traveling)

- Patrol (defending territory)

So when wolves finally find a herd of deer, elk, or caribou, they can’t just rush in blindly. They’re already in debt. Every chase has to be worth the cost.

You can explain it this way:

“Wolves don’t have snacks or grocery stores. Their only way to ‘refill’ is a successful hunt—so wasted chases are expensive.”

The Energy Equation of a Hunt

When a pack spots a herd in winter, it’s like opening a math problem:

Potential gain:

- One big animal = a lot of meat and fat

- ÷ shared among the pack

Potential cost:

- Getting close to the herd

- Testing which animals run how

- Any full-speed chase in deep or crusty snow

- Risk of injury from hooves, ice, or falls

Wolves don’t sit down and calculate, of course. But their behavior shows they’re always weighing the odds. You’ll often see them:

- Approaching, then backing off

- Testing the herd a few times

- Focusing on one weaker animal

- Abandoning chases that are going badly

One way to bring this to life for students is to tell the story of a single winter day as an “energy account.”

Imagine each wolf starts the day with 100 energy points:

- Traveling for hours to find prey: -20

- Circling to test a herd: -5

- A short burst to scatter the group and look for weak animals: -10

So before the “real” chase even starts, they’re already down to 65.

If they commit to a full chase through deep snow:

- Hard sprint in heavy snow: -30

Now each wolf has 35 points left.

If they succeed:

- One deer or elk taken down

- Shared meat and fat = +80 points

Net result: 115 points—slightly ahead of where they started.

If they fail:

- Prey escapes into thicker cover or safer ground

- No calories gained back

Net result: 35 points—far below where they started, and still hungry.

Same decision, two very different outcomes. That’s the gamble.

Snow: Sometimes a Helper, Sometimes a Trap

Snow doesn’t “belong” to wolves or to deer; it works on both.

On some days, snow gives wolves the advantage:

- Deep, soft snow makes it harder for hooved animals to run. Their narrow legs punch down, and they tire faster.

- Wolves, with longer legs and wide feet, can stay more on top of the snow. They can maneuver and change direction quickly.

On those days, a weak deer + deep snow can make a short chase very rewarding. A lot of energy in, but even more energy out.

On other days, snow fights back:

- Crusty or icy snow can cut paws and make running dangerous.

- Thin or patchy snow means prey can sprint more easily.

- Slippery surfaces increase the risk of falls and injuries for wolves too.

When conditions look bad, packs sometimes test the herd briefly and then move on—saving energy for a better chance.

A good classroom question here is:

- “Would you rather be the wolf or the deer in deep snow?”

- “What about on icy, hard-packed snow?”

Let students explain which side the snow is helping in each scenario.

Winter Prey Are Doing Their Own Energy Math

It’s easy to focus just on wolves, but prey animals are also living on tight budgets.

By late winter, deer, elk, or moose may be:

- Thinner from months of low food

- Moving through snow that costs extra energy

- Choosing when to run and when to stand their ground

For prey, “run every time you see a wolf” isn’t always the right answer. A panicked dash every hour would burn more energy than they can afford. Sometimes they:

- Watch the wolves

- Stay alert but still

- Only bolt when a predator gets very close or behaves differently

Now students can see both sides of the equation: two different species trying to solve the same problem—how do I make it to spring with enough energy left?

Turning Wolf Energy Math into Classroom Activities

Once students like the story, it’s easy to drop it into math, science, and writing.

1. Bar Graph: Good Hunt vs. Bad Hunt

Have each student (or group) track “wolf energy” for two days:

- Day 1: A successful hunt

- Day 2: A failed hunt

Give them starting energy (100), then use simple agreed-on “costs”:

- Traveling: -20

- Testing herd: -10

- Full chase: -30

Let them decide if the hunt succeeds or fails:

- If success: +80

- If failure: +0

Then:

- Draw a bar graph comparing starting energy vs. ending energy for each day.

- Talk about what happens if wolves have too many “failed hunt” bars in a row.

This makes “survival” feel very tangible.

2. Decision Game: Would You Chase?

Write three short hunt scenarios on the board, each with a bit of description.

Scenario A

- Prey: Young, limping deer

- Snow: Deep and soft

- Pack: Rested

- Distance: Close

Scenario B

- Prey: Strong adult elk

- Snow: Thin and icy

- Pack: Very tired

- Distance: Far

Scenario C

- Prey: Medium-strength deer

- Snow: Medium depth

- Pack: Moderately tired

- Distance: Medium

Ask students to choose for each one: CHASE or SAVE ENERGY

Then they justify in a sentence or two:

- “I would chase in A because the prey is weak and the snow helps the wolves.”

- “I would save energy in B because the elk is strong and the snow doesn’t slow it down much.”

You can underline that this is exactly the kind of decision wild animals “practice” every day—just without the written words.

3. Wolves vs. Humans: Two Ways to Handle Winter Energy

A simple Venn diagram helps students compare how we handle winter energy budgets versus wolves:

Wolves only:

- Get energy only from wild prey

- Spend huge energy on travel and chasing

- Can go days without successful hunts

- Can’t store food the way we do (no freezers!)

Humans only:

- Use houses, clothing, and heating to save energy

- Store food in pantries and refrigerators

- Can choose to drive instead of walk in the cold

- Can adjust work and rest times

Both:

- Must balance energy in vs. energy out

- Need shelter from extreme weather

- Make decisions about when effort is “worth it”

This makes “adaptation” feel less like a vocabulary word and more like a daily problem both wolves and humans solve in different ways.

Big Takeaway: Survival as a Moving Equation

By the end of the lesson, you can bring it all together like this:

“For winter wolves, every hunt is a math problem.

If they spend more energy than they gain, they’re in trouble.

If they choose their moments well, they can carry the whole pack through the hardest months of the year.”

Students see that:

- Predators aren’t just “chasing because they’re mean” — they’re trying to survive.

- Prey aren’t just “running scared” — they’re managing their own energy budgets.

- Snow isn’t just scenery — it’s a big factor in who spends and who saves.

And once kids start seeing energy math in wolf tracks, they’ll start spotting it everywhere: in owls listening over the snow, in bears deciding when to den, and even in their own choices about when to rest and when to push a little harder.