No Products in the Cart

Winter Is Owl Season: Why Cold, Dark Months Are the Best Time to Spot Owl

When most people think about watching wildlife, they picture warm evenings, leafy trees, and late sunsets.

Owls quietly disagree.

For them, the cold, dark months are prime time. Long nights, bare branches, and quiet neighborhoods actually make winter one of the best seasons of the year to find—and hear—owls, even if all you have is a sidewalk, a small park, or a nature center trail.

Once you see winter the way an owl does, you realize: the season we call “off” is very much on for them.

Let’s start with why winter tilts the odds in your favor, then move into some simple “little night walks” you can do from almost anywhere.

Why Winter Helps You Notice Owls

1. Bare Trees Turn Owls into Silhouettes

In summer, leaves swallow everything. An owl can sit ten feet above your head and vanish into the foliage.

In winter, those same branches become crisp black lines against the sky. An owl that would be completely invisible in July is suddenly:

- A rounded shape on a bare limb

- A set of ear tufts outlined against twilight

- A pale chest breaking the pattern of a trunk

You’re not looking into a wall of leaves anymore; you’re looking through a skeleton of branches. That alone makes winter a friend to anyone trying to spot an owl, whether you’re in a forest, a schoolyard, or a backyard with two decent trees.

2. Long Nights Mean More “Owl Time”

In June, you have to stay up late to meet owls.

In December, they’re active while many kids are still in their pajamas getting ready for bed.

Short days mean:

- Owls can start hunting earlier in the evening.

- Families and homeschool groups can go out briefly (after dinner) and still be home at a reasonable time.

- Nature centers and programs can run “owl nights” without pushing everyone into the middle of the night.

For nocturnal animals, long nights are like long work shifts. For us, they’re free extra hours when we can listen and look before the late-night tiredness hits.

3. Winter Quiet Makes Owl Voices Stand Out

Think about how your neighborhood or local park sounds in July:

Insects buzzing. Leaves rustling. People talking, mowing, playing. Dogs, sprinklers, air conditioners. It’s busy.

Now think about a cold, still winter evening:

No insects.

Few people out.

Bare branches barely moving.

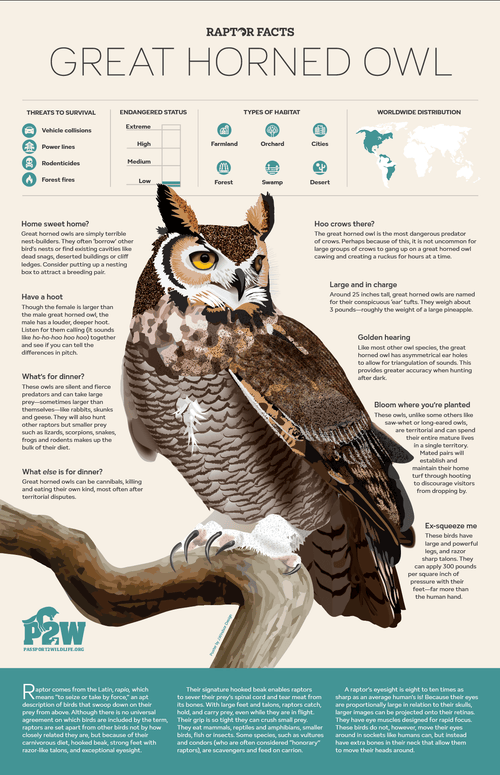

That “nothing’s happening” feeling is exactly what lets owl voices rise up. Deep great horned hoots, barred owl “Who cooks for you-all?” calls, and soft screech-owl trills travel farther and land more clearly in human ears.

Winter turns down the background volume. Owls get the microphone.

4. Prey Behavior in Winter Lines Up with Owl Hotspots

Even when fields are covered in snow and gardens look dead, there’s plenty of food moving around under and between things:

- Mice and voles running along fence lines and under snow crusts

- Rabbits working the edges of shrubs and brush piles

- Small birds coming and going from feeders

In other words, the same spots that feel “active” to you in winter—bird feeders, brushy corners, compost piles, barn edges, weedy field borders—are also where owls are likely to hunt.

If you’re trying to spot owls, winter quietly helps you out by concentrating prey into predictable places, which in turn concentrates owls along:

- Field edges

- Hedgerows

- Tree lines behind houses or schools

- Fencerows and ditch banks in farm country

You don’t need to hike miles. You just need to pay attention to the edges.

5. Late Winter: Owls Are Nesting Before the World “Wakes Up”

By the time we’re thinking about the first crocuses and spring break, many owls are already well into their nesting cycle.

Great horned owls in particular are famous for:

- Calling loudly in midwinter to defend territories

- Pairing up and choosing nest sites while snow is still on the ground

- Sitting tight on eggs in late winter, long before we’d call it “spring”

Other species also ramp up their calling as they bond with mates and settle into territories. That means January and February can be some of the most vocal months of the year.

The world still looks like winter.

The owls are acting like it’s spring.

For anyone listening, that’s a gift.

Little Night Walks:

How to “Go Owling” from Your Block, Park, or Nature Center

Once you know winter is working in your favor, you don’t need a big trip or a vast wilderness to “go owling.” A short, thoughtful walk from wherever you are can be enough.

Think of these as little night walks—20 to 40 minutes, close to home or your program, with no pressure to produce a dramatic sighting.

You’re not trying to chase owls. You’re trying to meet the winter night.

Step 1: Pick a Simple, Safe Loop

Start by choosing a route that works for your setting:

- A loop around the block or down one street and back for families

- A well-traveled park or greenbelt path for homeschool groups

- A short, clearly marked trail or road edge for nature centers and camps

You’re looking for:

- A mix of trees and open space (so you can see silhouettes against the sky)

- Reasonable lighting—dark enough to hear and see the sky, but safe

- Routes you already feel comfortable using with your group during the day

The key is familiarity. Winter night is different enough; everything else should feel easy.

Step 2: Set Expectations Before You Go

Before you step outside, it helps to say this out loud:

“We might not see or hear an owl tonight. That’s okay. We’re here to see what winter night is like where we live.”

That simple reset takes away the sense of failure if no owl appears.

Then add:

- What you will pay attention to: the shapes of trees, the feel of the air, any night sounds (dogs, cars, wind, maybe an owl).

- What counts as a success: spotting a good “owl tree,” hearing a distant hoot, or just noticing that the world feels different than it does during the day.

If you do hear an owl, that’s a bonus. If you don’t, you’ve still helped kids slow down and meet the dark in a friendly way.

Step 3: Walk Like Listeners, Not Explorers

On the walk itself, think more “quiet patrol” than “field trip.”

You don’t have to whisper, but try:

- Walking a little slower than usual

- Taking brief “quiet stops” where everyone listens for 30–60 seconds

- Looking up at tree lines, telephone poles, and the tops of barns or buildings

Ask simple, open-ended questions along the way:

- “If you were an owl, where would you sit to watch this place?”

- “Which tree here looks like a good hunting perch?”

- “Where do you think mice and rabbits might move at night?”

You’re training the human half of the brain to think like a night hunter, even if the actual owl stays offstage.

Step 4: Notice the Edges and the Evidence

On your route, pay extra attention to “edges” where two habitats meet:

- The line where a yard ends and woods begin

- The border between a field and a hedgerow

- The edge of a pond, creek, or drainage ditch

- The tree line around a parking lot or school field

These are the places where prey often moves—and where owls like to watch.

Depending on the ground and daylight, you can also look (or come back the next day) for sign like:

- Oval, grayish pellets beneath favorite roost trees

- Chalky white droppings (“whitewash”) on trunks or ground

- Feathers or tracks in snow

You don’t have to collect anything to make it real. Just pointing it out—“This is what an owl’s bathroom looks like”—connects the dots.

Step 5: Make a Quick Memory When You Get Home

After the walk, a five-minute follow-up locks the experience in place.

For families and homeschoolers, that might be:

- A quick sketch of the walk with one or two “best owl trees” marked

- A sentence or two in a nature journal: “Tonight I heard…” / “Tonight I noticed…”

- Looking at an owl poster or field guide together and asking, “If an owl were out there tonight, which one would it probably be?”

For nature centers, camps, and programs, it might be:

- A big shared map where each group adds a sticky note: “Heard a dog here, wind in the trees here, maybe an owl here.”

- A simple “night sound chart” kids can fill out while they warm up inside.

The point is not to create extra homework. It’s just to turn “We walked outside” into “We collected a memory and a little bit of data.”

You Don’t Have to See an Owl for It to Count

One of the most important messages you can give kids (and adults) is this:

“You can have a successful owl walk without ever seeing an owl.”

In winter, the advantages pile up: long nights, quiet air, bare trees, and vocal birds gearing up for nesting season. All of that makes this the best time of year to try.

Sometimes you’ll get the full story: a shadowy shape on a branch, a deep hoot rolling across the snow, pellets under a favored tree.

Other nights you’ll just get stars, cold air, and the realization that the world keeps going after the lights in the windows come on.

Either way, you’ve done something small and important:

You’ve shown that winter isn’t just a season to hide from.

It’s owl season—

and you know how to step outside and say hello.