No Products in the Cart

Polar Bears in Flip-Flops: What Happens When an Arctic Icon Lands Somewhere Warm?

Every winter, the same thing happens in classrooms and living rooms:

- Snowflake decorations go up.

- Hot cocoa shows up.

- And polar bears take over bulletin boards, winter pajamas, and cereal boxes.

Polar bears have become the unofficial mascot of “cold.” White fur, blue ice, drifting snow — we’ve locked them into that mental picture.

So let’s flip the script.

What if, instead of standing on sea ice under the northern lights, a polar bear woke up in a world where “winter” means rainstorms, mud, or 55°F and sunny?

What breaks first: the weather, the bear… or our assumptions?

Built for Ice, Not Sunshine

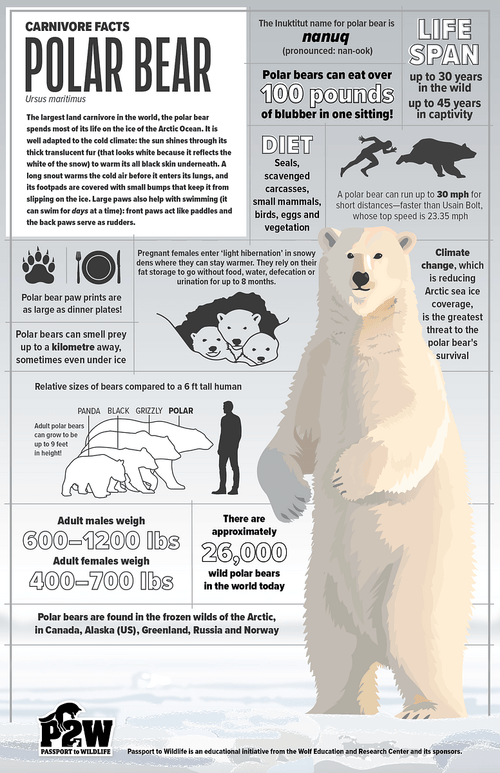

To understand why this thought experiment is so fun (and a little brutal), it helps to list what polar bears are built to do:

- Thick layer of blubber to stay warm in freezing air and icy water

- Dense fur that traps heat and sheds water

- Huge paws that act like snowshoes and paddles

- White-ish coat to blend in with snow and ice

- A body plan tuned to long swims and long fasting between seal meals

In the Arctic, these are superpowers.

In a warmer world?

They might start looking more like problems.

Imagine wearing your warmest winter coat, snow pants, wool socks, and a hat… into a crowded, heated indoor gym. That’s a bit what “too warm” might feel like to an animal who never evolved to cool down quickly.

Polar Bear in a Temperate Winter: What Changes?

Let’s say a polar bear doesn’t land in a tropical rainforest, but somewhere with “mild” winters — think coastal forests, rainy winters, or places where kids wear hoodies instead of parkas.

What would be different?

1. Overheating Becomes a Daily Problem

A polar bear’s body is so good at holding heat that even in the Arctic, they can overheat if they run too hard.

Drop that same body into:

- 50–60°F winter days

- Warmer water temperatures

- Less windchill and fewer cold, open expanses

…and suddenly just walking around could be costly. Instead of using energy to stay warm, the bear might be burning energy trying not to overheat.

You’d likely see:

- More resting in shade or water

- Shorter, cooler activity periods (dawn, dusk, night)

- A bear that looks “lazy” but is really carefully managing temperature

2. The Camouflage Problem

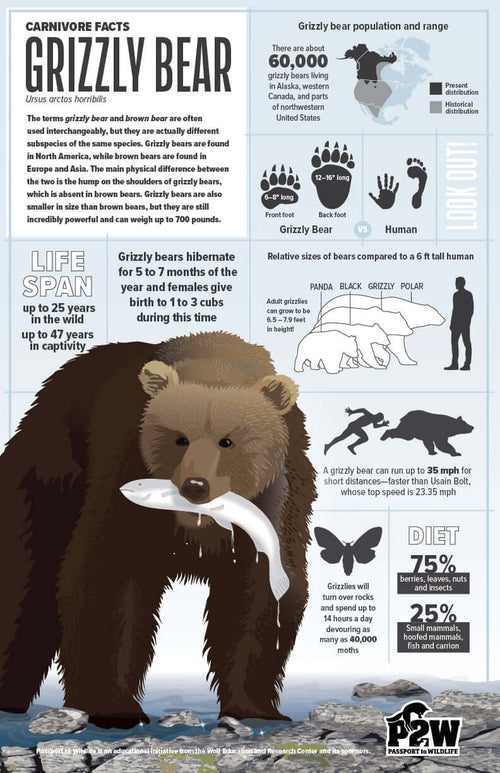

On snow and ice, polar bears are nearly invisible from far away. On dark rocks, brown dirt, or green grass?

They become giant, creamy-colored animals that stand out like a spilled milkshake.

The consequences:

- Prey might spot them sooner

- Stalking and ambush become harder

- Hunting efficiency drops — more energy spent, fewer calories caught

A predator that used to be a stealthy ghost on the ice becomes… a very obvious bear in the wrong outfit.

3. The Food Puzzle

In their real habitat, polar bears are marine mammal specialists, especially seals. Sea ice is their hunting platform.

In a warmer, not-so-icy place, three big questions pop up:

-

Where’s the fat-rich food?

Seals are calorie bombs. A bear that’s used to high-fat meals might struggle to replace those energy-dense foods with fish, bird eggs, or the occasional scavenged carcass. -

What’s the new hunting strategy?

No sea ice means:- No seal breathing holes to stake out

- Less predictable access to marine prey

- A shift toward land-based or coastal scavenging

-

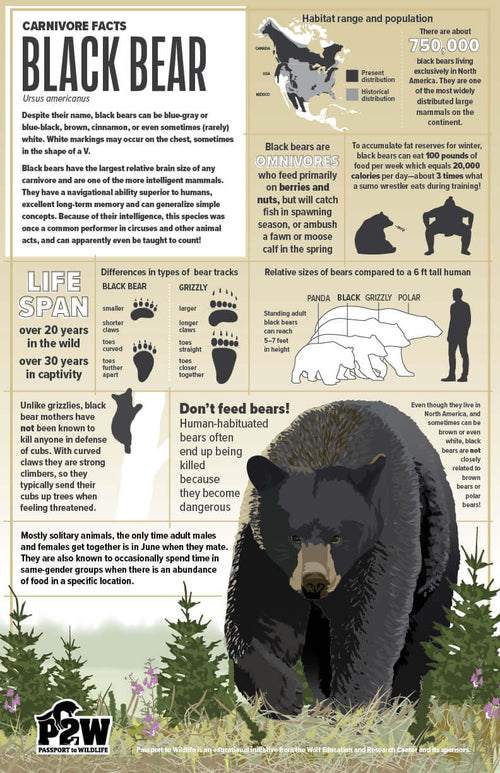

What about competition?

In a milder climate, other predators might already be doing very well — wolves, cougars, bears, big cats (depending on where you imagine this). A newly-arrived polar bear isn’t starting from zero; it’s starting behind.

So while it’s tempting to imagine a polar bear just “switching to fish and berries,” biology is rarely that easy.

The “Warm Bear” Isn’t Cute — It’s Complicated

In children’s books and decorations, we sometimes see polar bears in silly, warm places: beach towels, palm trees, sunglasses.

It’s a fun visual… but a good teachable moment.

You can gently explain:

- Polar bears aren’t “white brown bears.” They’re a separate species, highly specialized.

- Their entire life plan — hunting, breeding, resting — is tied to cold oceans and sea ice.

- Warmer isn’t “cozier” for them; it’s harder, riskier, and full of trade-offs.

Flipping the polar bear into a warm environment is a great way to ask:

“What happens when an animal’s superpowers don’t match its world anymore?”

That question works for every species lesson, not just bears.

Birds, Bears, and “Wrong” Seasons

You can pair polar bears with a second example to really drive home the concept of mismatch.

For instance:

- Snowy owls venturing farther south than usual in some winters

- Cold-water fish struggling in warming lakes

- Mountain animals that need snowpack and cooler slopes

Ask students:

- “If a snow animal has to live where there’s less snow, what gets harder?”

- “What part of its body or behavior stops making sense?”

Polar bears are just the clearest, most visual example of a bigger idea: wildlife is tuned very precisely to certain conditions.

Change the conditions too fast, and even a powerful animal can get pushed into a bad fit.

Classroom Connection: “Out of Place” Animal Match-Up

Here’s a simple activity that uses the flipped polar bear to build thinking skills.

Step 1: Pick Three Animals

Choose:

- Polar bear (Arctic, sea ice)

- Desert lizard (hot, dry)

- Tropical parrot (warm, forested)

Step 2: Pick Three Places

Draw or project:

- Arctic sea ice

- Desert dunes

- Tropical rainforest

Step 3: Mix Them Up

Ask students to:

- Match each animal to its “right” habitat.

- Then do the fun part: place each animal in the “wrong” habitat and answer:

- What would go wrong first?

- Could it survive even a week? A year?

- Which body features or behaviors become problems?

Encourage concrete answers:

- “The polar bear’s thick fur would make it overheat in the rainforest.”

- “The desert lizard might freeze on the ice because it has no fur and can’t make its own heat.”

- “The parrot might starve in the desert because there are no fruiting trees.”

You can end with:

“Animals don’t just live somewhere by accident. They are made for those places.”

A Gentle Way to Talk About Real-World Change

If your students are older or ready for deeper discussions, the flipped polar bear can also open doors to talking about:

- Changing sea ice

- Habitat shifts

- How long it takes species to adapt (or why some can’t in time)

You don’t have to make it heavy or scary. You can keep it focused on curiosity and observation:

- “What clues tell us an animal is in the wrong place?”

- “How might we know when a habitat is changing faster than animals can handle?”

Sometimes a simple, upside-down question does the heavy lifting:

“What if winter didn’t feel like winter anymore for a polar bear?”

The answers bring together everything — anatomy, behavior, food webs, climate, and empathy — in a way that sticks.

Takeaway for Winter

As your world leans into snowflakes, hot chocolate, and polar bear pajamas, you can remind your learners:

- Polar bears aren’t just winter mascots; they’re specialists built for a very specific cold world.

- Dropping them into a warm climate doesn’t make life easier — it actually removes the stage they’re meant to perform on.

- When we flip species into the “wrong” environment, we start to see how finely tuned nature really is.

And once kids see that, they’ll never look at a cartoon polar bear under a palm tree the same way again — in the best possible way.