No Products in the Cart

Owls Between Worlds: Northwest Native Legends, and Why Twin Peaks Couldn’t Let Them Go

There’s a reason owls feel like more than “just a bird” in the Pacific Northwest.

Out here, the forest is built like a cathedral—cedar pillars, moss hush, fog that turns headlights into halos. And when an owl calls in that kind of landscape, it doesn’t land as background noise. It lands as a message.

Across many Indigenous Nations of the Northwest Coast, owls show up in stories and teachings as beings tied to knowledge, warnings, and the boundary between worlds—sometimes respected as wise, sometimes treated with caution, often both at once.

And then, decades later, a television series set in a misty timber town gives us one of the most famous lines in modern PNW mythmaking:

“The owls are not what they seem.”

Let’s talk about why that line hits so hard—and how it echoes something much older than television.

Geography of the Nations We’ll Be Referring To

When I say “Northwest” here, I’m mainly talking about the temperate rainforest and coastal waters from the Salish Sea up through Southeast Alaska—and a few of the Indigenous Nations whose homelands are there.

- Coast Salish peoples: around the Salish Sea watershed (areas that now include Vancouver/Victoria in BC and Seattle/Puget Sound in WA).

- Kwakwaka’wakw: primarily the northeastern coast of Vancouver Island and nearby mainland British Columbia.

- Haida: centered on Haida Gwaii (BC) and also on parts of Prince of Wales Island in Southeast Alaska.

- Tlingit (Lingít): the rainforest coast of Southeast Alaska and the Alexander Archipelago, with communities also in BC and the Yukon.

These are distinct, living Nations with different languages and teachings—so “owl stories” don’t translate as one universal meaning across the entire Northwest.

Why Owls Fit the Northwest Coast So Perfectly

Owls are built for the liminal hours—the edges:

- dusk and pre-dawn

- forest edge and open field

- the line between visible and hidden

They move quietly, hunt precisely, and look straight through you like they’re reading footnotes.

That’s the biological reason.

The cultural reason is deeper: owls naturally become symbols for what we can’t fully see—the unseen, the unspoken, the not-yet-understood.

The Owl as a Messenger (and Why “Message” Doesn’t Always Mean “Comfort”)

In some Indigenous perspectives, owls are described as messengers, sometimes connected with ancestors and the spirit world. That “messenger” role can be gentle (guidance, awareness, protection) or intense (warnings, boundaries, grief). The same way a knock on the door at midnight can mean two very different things.

One Northwest Coast cultural center description (Kwakwaka’wakw context) captures this duality clearly: in dances, Owl can represent the “Wise One” and keeper of knowledge, and also be associated with ill-fortune and death warnings.

That’s the key: owls aren’t one-note. They’re layered—like the forest itself.

Owl = Knowledge Keeper (The Night Shift Librarian)

In the Kwakwaka’wakw “Animal Kingdom” dance tradition, Owl is described as the “Wise One” and keeper of knowledge.

Translation for the classroom: owls show up when a story needs a character who can move through darkness and still understand what’s happening.

Owl = Warning (A Boundary Marker, Not a Monster)

Some Northwest Coast sources describe owl presence or calls as connected to death or spiritual danger—again, not as a blanket statement for all Nations, but as a real theme in specific cultural contexts.

It’s important not to flatten this into “owls are bad” folklore. In many traditions, “warning” is not evil—it’s information. It’s the world telling you to pay attention, to be careful, to respect what you’re stepping into.

Sometimes the most caring thing a story can do is say: do not go farther.

Enter Twin Peaks: The Owl as Surveillance, Omen, and Doorway

Twin Peaks takes place in a Pacific Northwest mood-board: douglas firs, mist, timber, darkness that feels alive.

And it uses owls the way the region uses owls—like a living symbol.

The phrase “The owls are not what they seem” is delivered to Agent Cooper as one of the Giant’s cryptic messages. From there, owls become part of the show’s visual language—appearing around moments when something is off, hidden, or crossing over.

A lot of interpretation around the series suggests owls function like watchers—linked to the supernatural machinery of the woods and the Lodge mythos (the show never pins it down neatly, because Twin Peaks doesn’t do neat).

So what’s the connection to Indigenous owl meanings?

Not a direct line. Not a “this equals that.”

But thematically, it rhymes:

- Owls as messengers → Twin Peaks uses owls as carriers of meaning

- Owls as boundary markers → the show’s woods are literally a boundary space

- Owls as warnings → the owl often shows up when danger or distortion is near

That’s why the motif works. Lynch didn’t pick a parrot. He picked a creature the Northwest already reads as in-between.

What to Teach (Without Turning Living Cultures into Props)

If you’re bringing this into an educational setting, aim for media literacy + respect:

Classroom Connection: “Symbol vs. Species”

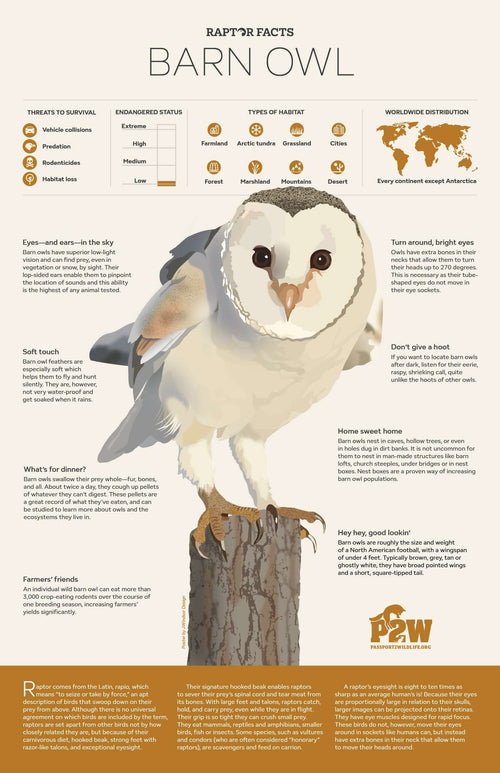

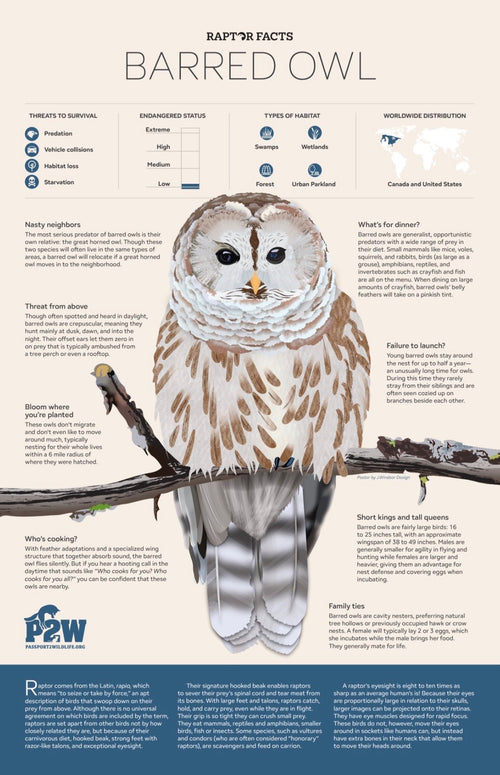

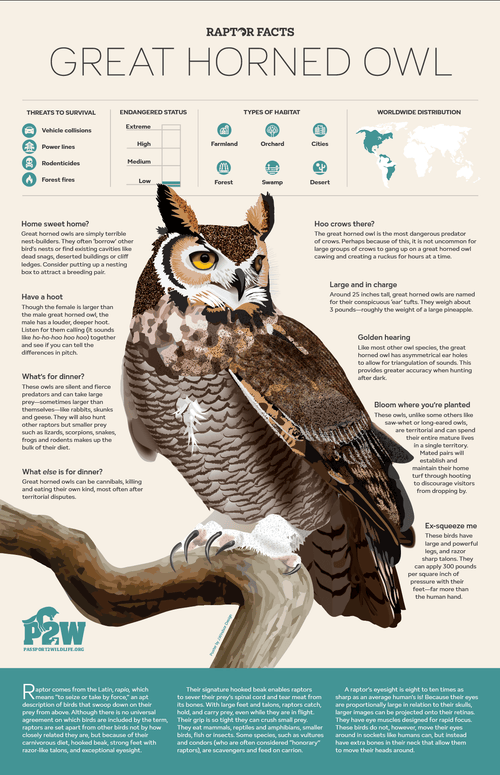

- Start with the animal: silent flight, nocturnal hunting, sensory adaptations.

- Discuss symbols carefully: “Different cultures interpret owls differently—sometimes as messengers, sometimes as warnings.” Use Nation-specific sources when you can.

- Then analyze Twin Peaks: “How does the show use the owl to communicate mood and meaning?”

Quick writing prompt

“If an owl is a messenger… what kind of message would it bring in a winter forest?”

Tell students they must label at least one sentence as observation and one as inference.

The Takeaway

In the Northwest, owls don’t just represent “nature.”

They represent thresholds—between light and dark, known and unknown, here and elsewhere.

That’s why they’re powerful in Indigenous stories (in varied, Nation-specific ways), and why Twin Peaks couldn’t resist them.

Because sometimes the most Pacific Northwest thing you can hear is a voice in the trees saying:

Pay attention. Something is happening.