No Products in the Cart

Grizzly Bears in America: The Power Animal That Still Shapes the Map

Grizzly Bears in America: The Power Animal That Still Shapes the Map

In the American imagination, the grizzly isn’t just a bear.

It’s weather.

It’s the sound a forest makes when something big is moving through it. It’s claw marks on a tree that feel like a sentence you’re not supposed to read out loud. And it’s a reminder that the wild isn’t a theme—it’s a living system with teeth, rules, and real consequences.

Grizzlies don’t simply live in a landscape.

They rearrange it.

First: What “Grizzly” Actually Means

Here’s the twist students (and a lot of adults) don’t expect:

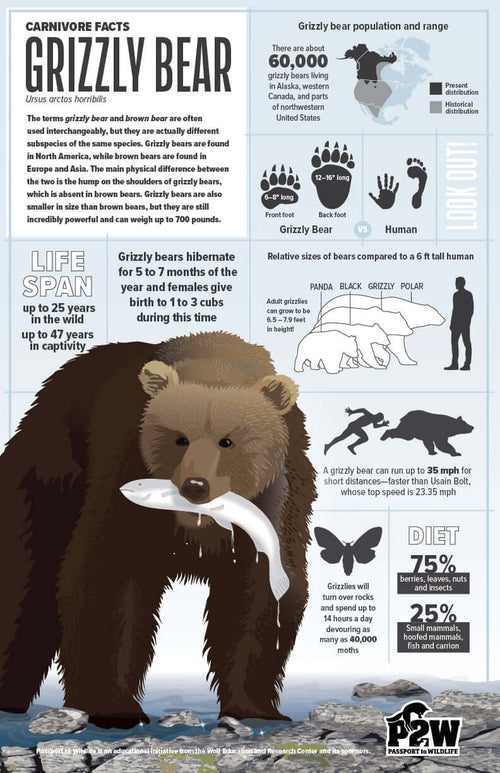

Grizzly bears and brown bears are the same species (Ursus arctos). In North America, “grizzly” usually refers to inland brown bears—often with that frosted-looking “grizzled” hair on the shoulders and back.

So when someone says “grizzly,” they’re often describing:

- a place (inland mountains, forests, tundra edges)

- a lifestyle (digging roots, flipping rocks, roaming huge territories)

- and sometimes a look (shoulder hump, dish-shaped face, darker-to-blond-tipped fur)

Grizzly is less a different bear… and more a different chapter of the same bear.

The Grizzly’s Real Job: “Apex Omnivore” (Not Just Predator)

Grizzlies aren’t strict carnivores. They’re opportunists with a strategy.

That means their menu changes with season and location:

- spring: roots, grasses, winter-killed animals

- summer: insects, berries, small mammals

- fall: nuts, fruit, meat when available

- coastal areas (where they overlap with salmon systems): high-calorie fish can become the headline

A grizzly’s superpower isn’t speed or stealth.

It’s flexibility.

And in a landscape with brutal winters and short growing seasons, flexibility is everything.

Why Grizzlies Matter: The Ecosystem Ripple Effect

If you want the “teacher version,” here it is:

Grizzlies are a living example of how one species can influence multiple layers of an ecosystem at once.

1) They move nutrients

When a grizzly drags a carcass, digs up roots, or hauls food into cover, it’s redistributing nutrients across the landscape—literally changing where energy ends up.

2) They plant seeds (yes, really)

Grizzlies eat a lot of fruit when it’s available. Seeds often pass through and get deposited far from the original plant—with built-in fertilizer.

3) They create micro-habitats

Digging for roots, bulbs, rodents, or insects disturbs soil. That disturbance can look destructive at first glance, but it also:

- aerates soil

- creates pockets for new plant growth

- changes insect communities

- opens space for other species

Grizzlies are not gentle.

But ecosystems aren’t built by gentleness alone.

Where Grizzlies Live in the U.S.

If you zoom out, grizzlies are mostly a western story in the contiguous U.S., plus a broader presence in Alaska.

They’re tied to:

- big, connected wildlands

- seasonal food corridors (berries, moth sites, carcass availability, river systems)

- and the kind of space most animals don’t require—space measured in mountain ranges

A key concept for students:

grizzlies don’t just need habitat. They need connected habitat.

The Human Factor: Why Grizzlies Became a Symbol and a Conflict

Grizzlies are iconic because they represent something Americans both admire and struggle to live beside:

- independence

- power

- unpredictability

- and the simple reality that you can’t “control” the wilderness if it still has grizzlies in it

This is where your lesson can get real without getting gloomy:

Grizzly conservation isn’t only about bears.

It’s about how humans manage food, space, waste, livestock, roads, and risk.

Grizzly stories always have two tracks:

- the bear track

- and the human track

And where those tracks overlap—that’s where the plot happens.

Field Signs: How You Know a Grizzly Has Been “Editing” the Landscape

Want a nature-detective angle? Grizzlies leave clues that feel like chapters:

- dig sites (soil tossed like a rototiller)

- flipped logs and rocks (for insects and grubs)

- tracks with a wide, heavy heel pad and long claw marks

- tree rubbing and claw marks

- scat that changes with the season (often berry-heavy later in the year)

This is a great reminder for students:

behavior leaves patterns.

And patterns are how science reads the wild.

Classroom Connection: “Grizzly Energy Budget” (A Math + Ecology Combo)

Grizzlies are perfect for an “energy budget” lesson because their whole life is about gaining enough calories to survive winter and reproduce.

Activity idea

Give student groups a “season card” and an “energy goal.”

- Goal: build 100 energy points before winter

- Food cards: berries, insects, roots, small mammals, scavenged meat, fish (depending on region)

- Each food type has a different energy value + time cost + risk cost

Then ask:

- Which foods are worth the effort?

- How does habitat change the menu?

- What happens when humans accidentally provide food (garbage, pet food, unsecured attractants)?

- How does that shift bear behavior and risk?

Students will discover the big truth on their own:

the easiest calories are often the most dangerous calories.

Writing Prompt: “Two Tracks, One Valley”

Have students write a short piece with two perspectives:

- a grizzly moving through a valley across seasons

- a human community living in the same valley

Rules:

- include 3 factual ecology details (diet shift, habitat need, behavior sign)

- include 2 “conflict points” and 2 “solutions”

- label one sentence observation and one sentence inference

It turns “bears are scary” into “bears are part of a system.”

The Takeaway

Grizzlies are not just American wildlife.

They’re American scale—a species that forces us to measure the land differently, plan differently, and tell the truth about what “wild” actually means.

If owls are the Northwest’s whisper—

grizzlies are the part of the forest that says, calmly:

This place still belongs to something bigger than you.

```